A study conducted during the 1996 U.S. presidential election cycle found that Democratic nominee President Bill Clinton’s primary personality patterns are Asserting/self-promoting (subsequently relabeled Ambitious/self-serving) and Outgoing/gregarious. A dimensional reconceptualization of the results to examine convergences among the Millon-based personality profile, Simonton’s dimensions of presidential style, and the five-factor model suggested that Clinton was predominantly charismatic/extraverted.

A study conducted during the 1996 U.S. presidential election cycle found that Democratic nominee President Bill Clinton’s primary personality patterns are Asserting/self-promoting (subsequently relabeled Ambitious/self-serving) and Outgoing/gregarious. A dimensional reconceptualization of the results to examine convergences among the Millon-based personality profile, Simonton’s dimensions of presidential style, and the five-factor model suggested that Clinton was predominantly charismatic/extraverted.

The Clinton Chronicle: Diary of a Political Psychologist (Aubrey Immelman, 1998-99) — On December 19, 1998 William Jefferson Clinton became only the second U.S. president to be impeached by the House of Representatives. This article is a chronicle, from my perspective as a political psychologist, of debates and controversies in the unfolding of this national drama. The curtain rises as the president prepares on August 17, 1998 to testify before the grand jury in the Starr investigation. The narrative proceeds to the final act as the Senate acquits the president on February 12, 1999 on articles of impeachment brought by the House. But this nightmarish production has no final curtain, as Washington persists in practicing its poisonous partisan politics of personal destruction and as charges of sexual assault more than two decades earlier are leveled against Bill Clinton. … Full report

Research reports

The Political Personalities of 1996 U.S. Presidential Candidates Bill Clinton and Bob Dole (Aubrey Immelman, The Leadership Quarterly, Vol. 9, No. 3, Special Issue: Political Leadership, Fall 1998, pp. 335–366). Full text available at Digital Commons: https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/psychology_pubs/3/

A Comparison of the Political Personalities of 1996 U.S. Presidential Candidates Bill Clinton and Bob Dole (Paper presented by Aubrey Immelman at the 19th Annual Scientific Meeting of the International Society of Political Psychology, Vancouver, BC, June 30–July 3, 1996). Full text available at Digital Commons: https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/psychology_pubs/39/

“All the Men’s President” — The Political Personality of Bill Clinton (Aubrey Immelman, The Saint John’s Symposium, Vol. 13, 1995, pp. 36–46). Full text available at Digital Commons: https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/psychology_pubs/22/

Book review

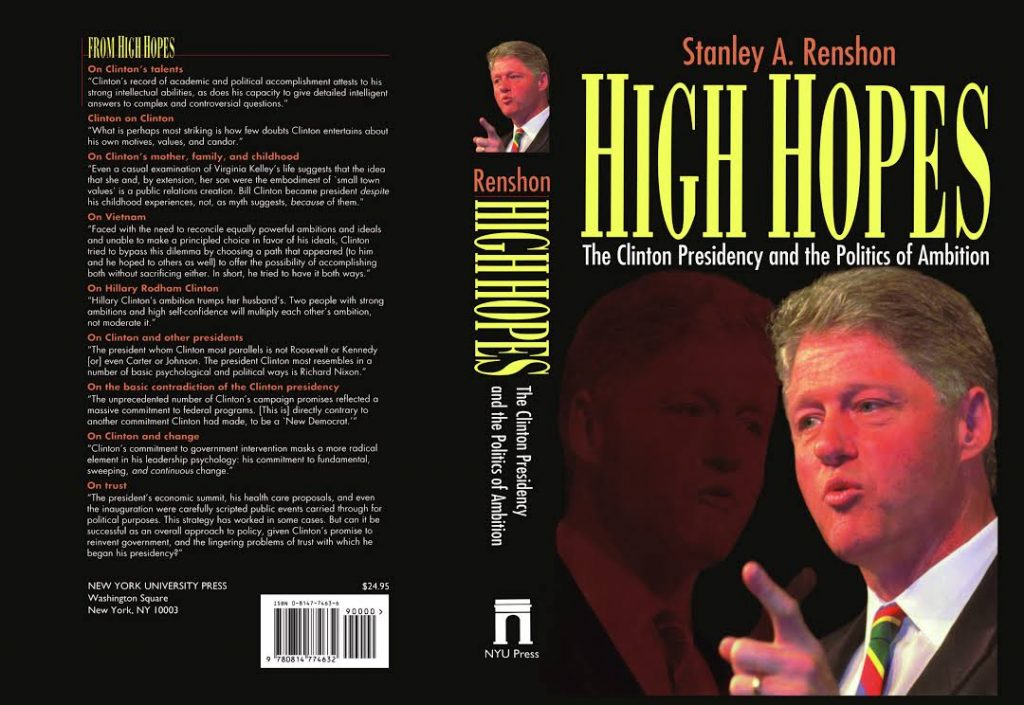

“High Hopes: The Clinton Presidency and the Politics of Ambition” by Stanley A. Renshon (Aubrey Immelman, Political Psychology, Vol. 18, No. 2, Special Issue: Culture and Cross-Cultural Dimensions of Political Psychology, June 1997, pp. 535–539).

Related opinion column

Personality Scrutiny Brings Fewer Presidential Surprises (Aubrey Immelman, St. Cloud Times, March 11, 2000, p. 7B) — It will be unfortunate if the current investigation of President Clinton’s controversial executive pardons of Marc Rich and others culminates in little more than a partisan game of “gotcha” politics. Even an outcome that results in better checks and balances with respect to the president’s pardon power would be of questionable value. Do we really want to abridge the constitutional powers and prerogatives of the president on the strength of — to quote Senate doyen Robert Byrd — the “malodorous” actions of a president no longer in office? … Full report

Related article

The Man from Hope: Profiling Bill Clinton

How mental health professionals have sized up the president’s personality

By John Martin-Joy, M.D.

![]()

September 26, 2020

Excerpts with names of cited scholars bolded for emphasis

[ . . . ]

Even before impeachment, mental health professionals wasted no time in probing Clinton’s psychology. Beginning as early as 1994, psychologist David Winter was examining the content of Clinton’s major speeches for clues to his personality.

Clinton, Winter concluded, was an idealist who was motivated primarily by achievement. Such an orientation, however, tended to predict frustration rather than success in the presidency. In contrast, Winter asserted that power motivation—a love of the vicissitudes of the political process itself—was the best predictor of success. A playfulness like that of Franklin Roosevelt or John F. Kennedy was the royal road to political success.

A version of Winter’s assessment later appeared in Jerrold Post’s edited collection The Psychological Assessment of Political Leaders (2003). This remarkable volume probed Clinton’s psychology in depth. Contributors used a comparative approach (the book also examined Saddam Hussein of Iraq), drew on multiple sources, employed empirical rating scales, and in general deployed much professional rigor.

Going through the book today, one is struck by the depth and methodological care that the book’s contributors, all experienced in studying political leadership, brought to their task.

Psychiatrist and psychoanalyst Stanley Renshon, for example, explored what he saw as the central components of Clinton’s character: ambition, integrity, and relatedness. Using a psychodynamic approach and building on his own award-winning 1996 book, he postulated that Clinton’s character grew from his complex relationship with his mother Virginia. Renshon reviewed the Clinton marriage and identified Bill Clinton’s alleged ambition, impatience, persistence, and need to be special as important motives in his rise to power.

Psychoanalyst and political scientist Walter Weintraub looked closely at Clinton’s press conferences. In them, Weintraub found a high ratio of “I” and “me” statements to “we” statements, a ratio that to him suggested something distinctive: that Clinton saw himself as a leader who could get things done rather than the leader of an ideological crusade. Weintraub also saw a propensity in Clinton to assume “the victim role when attacked.” And Peter Suedfeld and Philip Tetlock looked closely at the quality of “integrative complexity” (flexibility, openness to ambiguity and to potentially conflicting ideas) as it applied to Clinton as decision-maker.

Renshon sounded a characteristic note of caution: In profiling public figures, “measured prudence” was preferable to “theoretical enthusiasm.”

It was a warning that few psychological commentators on presidents would heed in the years ahead.

Psychologist John Gartner, an open enthusiast for an idea, used an altogether different approach in his later book In Search of Bill Clinton (2008). The book aimed for a general readership rather than an academic one. And it was the product of two years of deep immersion in Clinton’s world.

Gartner did not use empirical methods. Instead, he relied on extensive interviews. His project elicited cooperation from many friends and associates of Clinton’s, including staffers, friends of Clinton’s mother, and journalists who had covered the president for decades. In all, the psychologist conducted 100 interviews in an effort to understand the man. Gartner also had two brief public interactions with Clinton himself.

Gartner called his method “psycho-journalism.”

Gartner’s idea was that Clinton had a “hypomanic temperament.” Explored at length in a previous Gartner book, the hypomanic temperament is a chronic high-energy state in which a person has “immense energy, drive, confidence, visionary creativity, infectious enthusiasm, and a sense of personal destiny”—not to mention impulsivity. Gartner carefully differentiated this temperament from similar-sounding relatives: a hypomanic episode and bipolar mania. He concluded that the hypomanic temperament is the key to Clinton’s striking combination of strength and vulnerability.

The argument was not unprecedented.

The hyperthymic personality, which appears similar to Gartner’s construct, is familiar to many clinicians. In 1996, psychologist Aubrey Immelman’s empirical research findings about Clinton [hyperlink added] suggested something arguably similar: an asserting/self-promoting and outgoing/gregarious personality type. In 2011 psychologist Dan McAdams, in comparing Clinton to George W. Bush, saw both as extraverts. And psychiatrist Nasser Ghaemi has long argued for the value of depression and bipolar disorder to some success in politics and in life. (In a review Ghaemi found Gartner’s previous book “one-dimensional” and superficial in its approach to bipolar disorder and related states.)

[ . . . ]

These efforts at psychological understanding from a distance, whatever their merits, have obvious limits.

Neither Post’s volume nor Gartner’s substantially addresses the ethics of evaluation from a distance. Yet none of Post’s contributors interviewed Clinton; none obtained his permission for their evaluations. Gartner’s two encounters with Clinton took place in public and lasted only a few seconds each: he shook hands with Clinton on one occasion and asked him one question on another.

Post himself is the profession’s major contributor to the question of the ethics of such comment. His argument, advanced elsewhere, is that the risks of comment on public figures must be weighed against the benefits to public education and public safety. For example, informing the public about a national danger related to a leader’s mental state may make the effort ethical. No such danger is documented in these books.

Bill Clinton’s fascinating complexity represented a turning point in the psychological evaluation of leaders from a distance in America. In the Clinton years and after, the practice of comment from a distance would become almost routine.

Admittedly, few of us can devote the time and care that Gartner devoted to his interviews and assessment of Bill Clinton. But more and more, the mental health professions continue to see clearly from a distance—and to try to get it right.

[ . . . ]

John Martin-Joy, M.D., is a psychiatrist in private practice in Cambridge, Massachusetts. He is the author of Diagnosing from a Distance (Cambridge University Press, 2020) and a candidate at the Boston Psychoanalytic Society and Institute.

Follow Aubrey Immelman