Psychological Profile of Saddam Hussein

The Psychological Profile of Saddam Hussein

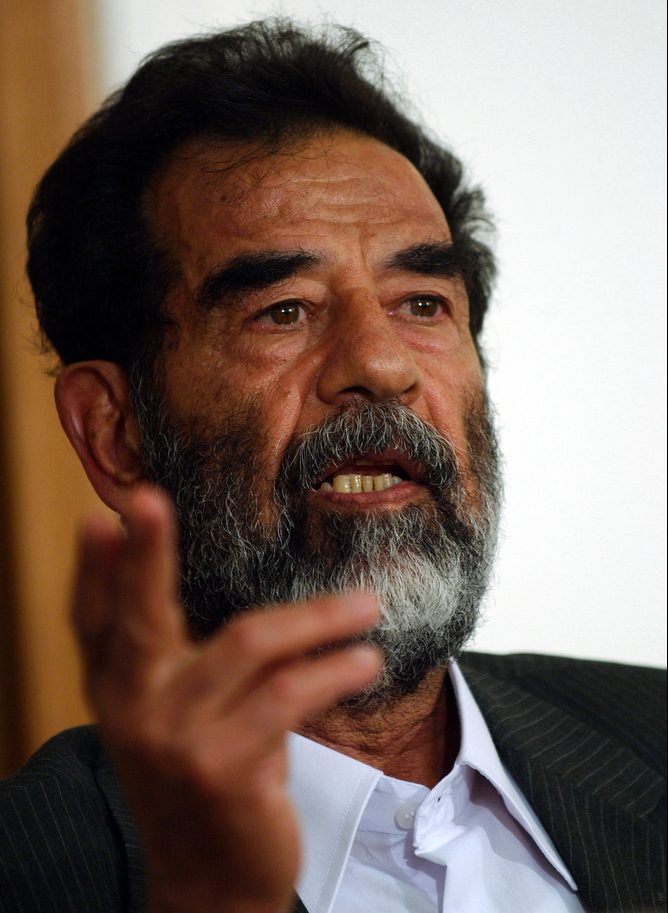

Former Iraqi President Saddam Hussein

By Aubrey Immelman

March 2003

Saddam Hussein’s psychology can be described in terms of the syndrome of “malignant narcissism.” The core components of this syndrome are pathological narcissism, antisocial features, paranoid traits, and unconstrained aggression.

Pathological narcissism

Saddam exhibits pathological narcissism, a personality pattern characterized by extreme grandiosity, overconfidence, and self-absorption to a degree that renders one incapable of empathizing with the pain and suffering of others. Leaders with this profile are devoid of empathy and unmoved by human suffering, which permits them to commit atrocities against their own people as readily as they are willing to brutalize their enemies.

This aspect of malignant narcissism parallels a pattern that Theodore Millon (Millon, 1996, pp. 409–410; Millon & Davis, 1998, p. 162; Millon & Davis, 2000, pp. 277–278) has labeled unprincipled narcissism or unprincipled psychopathy.

Unprincipled, narcissistic leaders exhibit an arrogant sense of self-worth, an indifference to the welfare of others, and a fraudulent social manner. There is a desire to exploit others or at least an expectation of special recognition and consideration without assuming reciprocal responsibilities. A deficient social conscience is evident in a tendency to flout conventions, to engage in actions that raise questions of personal integrity, and to disregard the rights of others. They justify audacious acts with expansive fantasies and frank prevarications.

Descriptively, these leaders may be characterized as being devoid of a superego – that is, as evidencing an unscrupulous, amoral, and deceptive approach to relationships with others. Disloyal and exploitative in the extreme, they share qualities commonly associated with society’s con artists and charlatans, many of whom are vindictive toward and contemptuous of their victims. They display an indifference to truth that, if exposed, is likely to elicit an attitude of nonchalant indifference. They are skillful in the ways of social influence, facile in feigning an air of justified innocence, and adept at guilefully deceiving others with their charm and glibness. Lacking any deep feelings of loyalty, they may successfully scheme beneath a veneer of politeness and civility. Their principal orientation is that of outwitting others – “Do unto others before they do unto you.” They attempt to present an image of nonchalance or cool strength, acting arrogantly and inviting danger and punishment. With their devious and guileful style, they are constantly plotting and scheming in their calculations to manipulate others. They are self-centered, indifferent to the needs and rights of others, and adept at preying on the weak and vulnerable.

These leaders predictably evidence a rash willingness to risk harm and are usually fearless in the face of threats and punitive action. Malicious tendencies are projected outward and vengeful gratification is obtained by humiliating others. They operate as if they have no principles other than exploiting others for their personal gain. Lacking a genuine sense of guilt and possessing little social conscience, they are opportunists who enjoy the act of outwitting or swindling others, whom they hold in contempt because of the ease with which they can be seduced. Relationships and agreements survive only as long as they have something to gain from the arrangement. People and allies are abandoned with no thought to the anguish or injury that may result from their self-serving and irresponsible actions.

Antisocial (psychopathic) features

The tenuous social conscience of malignant narcissists is governed primarily by self-interest. Malignantly narcissistic leaders like Saddam are driven by power motives and self-aggrandizement; however, their antisocial amorality permits them to exploit the principled beliefs and deeply held convictions of others (e.g., religious values or nationalistic fervor) to consolidate their own power. They are undeterred by the threat of punishment, which makes them singularly resistant to economic inducement, sanctions, or any other pressures short of force.

This aspect of malignant narcissism parallels a pattern that Theodore Millon (Millon, 1996, p. 451; Millon & Davis, 1998, pp. 164–165; Millon & Davis, 2000, pp. 110–111) has labeled covetous psychopathy or the covetous antisocial.

Covetous, antisocial leaders are fundamentally aggrandizing. They feel that life has not given them their due – that they have been deprived of their rightful measure of emotional sustenance or material rewards and that others have received more than their rightful share. Thus, they are driven by envy and a desire for retribution – a wish to take for themselves that of which they have been deprived. These goals can be achieved by the assumption of power, and it is best expressed through avaricious greed and voracity. Through acts of theft, destruction, or deceit, they compensate themselves for the emptiness of their own lives, dismissing with smug entitlement their violations of the social order.

For these leaders, the usurpation of others’ earned achievements and possessions becomes their highest reward. This pattern is self-perpetuating, because gratification is achieved in taking rather than possessing. These individuals have an enormous predatory drive. They manipulate others and treat them as pawns in their quest for power, showing minimal empathy for those who are exploited and deceived. Although they have little compassion for the effects of their rapacious behaviors, feeling little or no guilt or remorse for their actions, at base they remain uncertain about their power and possessions; they never feel that enough has been acquired to compensate for past deprivation. Regardless of their achievements, they remain ever jealous, envious, and greedy, presenting ostentatious displays of materialism and conspicuous consumption. For the most part, they are entirely self-centered and self-indulgent, often profligate and wasteful, unwilling to share with others for fear of relinquishing what was so desperately desired earlier in life. Hence, rather than achieving gratification and contentment, they remain unfulfilled and empty, regardless of their successes, remaining forever implacable and unappeased.

A paranoid outlook

Behind a grandiose façade, malignant narcissists like Saddam harbor a siege mentality. They are insular, project their own hostilities onto others, and fail to recognize their own role in creating foes. These real or imagined enemies, in turn, are used to justify their own aggression against others.

This aspect of malignant narcissism parallels a pattern that Theodore Millon (Millon, 1996, pp. 707, 717–718; Millon & Davis, 1998, p. 170; Millon & Davis, 2000, p. 380) has labeled malignant paranoia or malignant psychopathy.

Malignant, paranoid leaders are power hungry, mistrustful, resentful, and envious of others. Intimidating and belligerent, they are consumed by a ruthless desire to avenge past wrongs and to triumph over others – by cunning revenge or callous force, if necessary. Through the intrapsychic mechanism of projection, they attribute their own venom to others, ascribing to them the malice and ill will they feel within themselves. Their persecutory beliefs may assume almost delusional proportions.

The defining feature of malignant paranoia is an intense power orientation and a concomitant need to resist all outside influences. These leaders cling tenaciously to their independence and the belief in their own self-worth. Criticism is seen as maliciously motivated to intimidate, offend, and undermine their self-esteem – to thwart their talents, to spread lies, to destroy their power, and to subjugate them to the will of others. These leaders dread losing their self-determination; their persecutory fantasies are filled with fears of being forced into submission and of being tricked to surrender their autonomy.

Unconstrained aggression

Malignant narcissists like Saddam are cold, ruthless, sadistic, and cynically calculating, yet skilled at concealing their aggressive intent behind a public mask of civility or idealistic concern.

This aspect of malignant narcissism parallels a pattern that Theodore Millon (Millon, 1996, pp. 453–454; Millon & Davis, 1998, pp. 168–169; Millon & Davis, 2000, pp. 112–113) has labeled malevolent psychopathy or the malevolent antisocial.

Sadistically malevolent leaders are noted for being particularly vindictive and hostile. Their impulse toward retribution is discharged in repugnant and destructive defiance of conventional social life. The sadistic characteristics of these individuals blend with their antisocial and paranoid tendencies, reflecting not only hostility, but intermingling with a deep sense of deprivation and an intense desire for compensatory retribution. Distrustful of others and anticipating betrayal and punishment, they have acquired a cold-blooded ruthlessness, an intense desire to gain revenge for the real or imagined mistreatment to which they were subjected in childhood. There is a sweeping rejection of tender emotions and a deep suspicion that the goodwill efforts expressed by others are merely ploys to deceive and undo them. They assume a chip-on-the-shoulder attitude, a readiness to lash out at those whom they distrust or those whom they can use as scapegoats for their seething impulse to destroy.

Descriptively, these leaders may be characterized as belligerent, mordant, rancorous, vicious, malignant, brutal, callous, truculent, and vengeful. They are distinctively fearless and guiltless, inclined to anticipate and search out betrayal on the part of others. Dreading that others may view them as weak or manipulate them into submission, they rigidly maintain an image of hard-boiled strength, carrying themselves truculently and acting tough, callous, and fearless. To prove their courage, they may court danger and punishment. But punishment will only verify their anticipation of unjust treatment. Thus, rather than being a deterrent, punishment may reinforce their rebelliousness and their desire for retribution. In exercising power, they often brutalize others to confirm their self-image of strength. If faced with failure or beaten down in their efforts to dominate and control, their feelings of frustration, resentment, and anger may mount to a point where their controls give way to raw brutality or vengeful hostility. Driven by a need for power and retribution, aggressive impulses may surge into the open. At these times, their behaviors may become outrageously and flagrantly sadistic and antisocial. Though capable of understanding guilt, they are unable to experience remorse, displaying instead an arrogant contempt for the rights of the others. They relish in menacing others, making them cower and withdraw. They are combative and seek to bring more pressure to bear on their opponents than their opponents are willing to tolerate or to exert against them.

These leaders make few concessions and are inclined to escalate violence as far as necessary, refusing to relent until others succumb. Nonetheless, these malevolent leaders recognize the limits of what can be achieved in the service of their own ambitions. They do not lose self-conscious awareness of their actions and will press forward only if their aggrandizing ambitions are likely to succeed. Thus, their adversarial stance is often contrived, a bluffing mechanism to ensure that others will back off first. However, occasionally overconfidence may lead them to misjudge their adversary, inviting effective counterreaction.

Political implications

Because self-aggrandizement is the guiding force that drives Saddam, the only plausible scenario under which he would voluntarily relinquish political power would be the conviction that it would give him a “second lease on life” and permit him to survive the current crisis, ultimately to return to power. His personality profile suggests that Saddam Hussein will use all means at his disposal to cling to power. If backed into a corner, he may take his own life rather than surrender.

References

Millon, T. (with Davis, R. D.). (1996). Disorders of personality: DSM-IV and beyond (2nd ed.). New York: Wiley.

Millon, T., & Davis, R. D. (1998). Ten subtypes of psychopathy. In T. Millon, E. Simonsen, M. Birket-Smith, & R. D. Davis (Eds.), Psychopathy: Antisocial, criminal, and violent behavior (pp. 161–170). New York: Guilford.

Millon, T., & Davis, R. D. (2000). Personality disorders in modern life. New York: Wiley.

Follow Aubrey Immelman