Theories on personality pan out

Editor’s note: In the past year, Times columnist Aubrey Immelman has argued that presidential candidates’ personality profiles serve as useful predictors of their performance in office. As this drawn-out election drags to a close, Immelman uses this column to provide accountability for his personality-based political analysis.

By Aubrey Immelman

St. Cloud Times

December 10, 2000

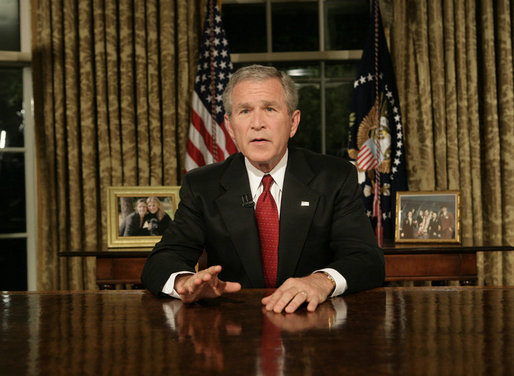

Public domain

In my opinion columns during the past election year, I contended that presidential candidates’ personality profiles predict their performance in office.

A practical, preliminary test of this contention is to examine how my personality-based predictions for Vice President Al Gore and Texas Gov. George W. Bush fared in foreshadowing their actual behavior during the 2000 presidential campaign.

On Aug. 13 I wrote that Gore, though diligent and dutiful, was inclined to be stubborn and moralistic — a classic conscientious type.

When combined with considerable aloofness, the less endearing aspects of the conscientious character can compound the candidate’s public relations problems.

As I noted, introverts like Gore are not particularly warm or engaging, and their lack of social graces may be “perceived as social indifference and a lack of empathy, which tends to elicit a reciprocal reaction in voters.”

This is exactly what happened in the first presidential debate, “which the overeager, socially tone-deaf Gore won on raw debating points but lost in the court of public opinion,” I ventured on Nov. 19.

And it is precisely this politically debilitating combination of deep introversion and being too conscientious that moved New York Times columnist Maureen Dowd to lament Nov. 22, “Truth to tell, some of Mr. Gore’s own campaign aides don’t even like him because he’s so aloof and hypercritical. As one Democrat despaired before the election, ‘If his aides don’t like him, how can they possibly sell him to the rest of the country?'”

George W. Bush, too, proceeded predictably. His principal strength as an outgoing candidate would be his skill in mobilizing popular support and retaining a following in the face of adversity.

And Bush’s primary leadership limitations, I suspected, included a superficial grasp of complex issues, impulsiveness, and a propensity for favoring personal connections, friendship and loyalty over competence in his staffing decisions and political appointments.

This assessment was largely borne out in the course of the campaign. Bush demonstrated his strengths as a mobilizer by erasing Gore’s post-convention bounce. And afterward, Bush outflanked Gore on the public relations front of their running battle for Florida’s contested electoral votes.

However, Bush’s personal deficits made him vulnerable not only to his adversary’s attacks, but to self-inflicted wounds. Gore’s most effective weapon against Bush was the charge that he lacked the capacity to be president, and Bush never quite convinced his critics that he was fully in command of the issues.

Most telling was the way Bush predictably stumbled into the pitfall of personal connections and loyalty in his personnel decisions.

Bush’s selection of Dick Cheney as his running mate — the very person charged with leading his vice-presidential search, and secretary of defense in his father’s administration — offered an early glimpse of this proclivity.

More disconcerting, Bush’s decision to withhold information about his 1976 drunken driving arrest was probably the most momentous miscalculation of his presidential campaign. Incredibly, key members of Bush’s inner circle reportedly had been aware of this time bomb yet failed to impress upon their boss the importance of coming clean. This critical lapse of judgment quite conceivably cost the candidate the votes he needed for a popular-vote victory.

As I wrote Jul. 30, “the erratic path of George W. Bush’s coming-of-age as a politician … [raises] legitimate questions concerning his … judgment.”

Gore, for his part, had problems of his own. Most notably, the tenacity with which he clung to the rapidly receding prospect of victory following Bush’s certification as the winner in Florida, and his reluctance to concede, could spell the end of his political career.

On Aug. 13, I wrote that high-dominance introverts like Gore tend to view the world in terms of a struggle between “the moral values they think it ought to exhibit and the forces opposed to this vision.” They seek “to reshape the world in accordance with their personal vision,” favoring impersonal mechanisms and moral principles toward this end.

In short, Gore had “a self-defeating potential for dogmatically pursuing personal policy preferences despite legislative or public disapproval,” coupled with “a deficit in the politically pivotal skill of easily connecting with people.”

Glimmerings of this tendency could be discerned in Gore’s no-holds-barred struggle for political survival in Florida, despite rising unfavorability ratings and increasingly urgent calls that he concede defeat.

Ultimately, the uninspiring Gore’s slim majority of the popular vote stands as testimony not of his strength as a candidate, but of the prosperous economy and the collective contentment of the American people. Bush’s points-advantage in personality effectively canceled Gore’s political edge, yielding an electoral tie.

But no matter who is finally declared the winner, the new president will face an uphill struggle. The obstacles for Gore would be more daunting. Practically, he will face Republican majorities in both the House and the Senate. Personally, his introversive nature serves as an impediment to the kind of compromise, coalition building, and forging of supportive networks indispensable in institutionalizing his policy initiatives.

Although Bush for his part will be considerably hampered by the slender margin of the congressional Republican majority, his less ideological, more conciliatory, outgoing orientation will augment his “retail” politician’s skills and catalyze his capacity to consummate his policy objectives.

But whatever happens, the 43rd president of the United States will be cursed with a cloud of skepticism concerning the legitimacy of his election.

Aubrey Immelman is a political psychologist and an associate professor of psychology at the College of St. Benedict and St. John’s University. You may write to him in care of the St. Cloud Times, P.O. Box 768, St. Cloud, MN 56302.

Follow Aubrey Immelman