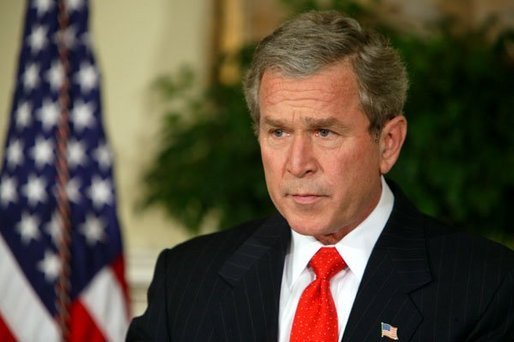

Getting inside the Bush mind

By Aubrey Immelman

St. Cloud Times

December 17, 2000

With the legal wrangling behind us, and George W. Bush poised to assume the presidency, it’s pertinent to ask how the newly elected president will govern.

The short answer can be framed in terms of party, policy and promises. Bush is a Republican. That has to count for something. In addition, the president-elect enunciated specific policy positions in the course of his campaign. Naturally, he will pursue these initiatives. Finally, Bush will try to make good on his campaign promises. The calculus of politics demands that much.

More complex analysis must account for larger structural, situational and institutional forces. Congressional Republican majorities will assist the new president in consummating his policy objectives, but the fragile Republican margin and a weak electoral mandate will impose considerable constraints.

With regard to predicting the tenor of Bush’s presidency, suffice it to say that there will be no shortage of commentary and analysis zeroing in on these considerations.

More difficult to fathom, yet equally important, is the role of character and other personal qualities in shaping presidential performance.

What follows is an early assessment of President-elect Bush’s likely leadership style and policy preferences, based on his distinctively outgoing, extraverted personality, and using the framework provided by Princeton political scientist Fred Greenstein in his book, “The Presidential Difference.”

Public communication

The modern presidency, according to Greenstein, places a premium on “the

teaching and preaching side of presidential leadership.” The best public communicators among postwar presidents — Roosevelt, Kennedy, Reagan and Clinton — were all outgoing presidents; however, Bush lacks their rhetoric skills.

But, as Greenstein notes, eloquence is partially a product of effort and experience. Bush may lack the diligence and discipline to be a quick study in soaring public oratory, but will no doubt improve with time, just as he refined his debating skills in the presidential campaign.

Organization

Bush’s personality does not provide the optimal basis for organizational strength, though he will likely improve on what Greenstein calls the “oxymoronic organization of the Clinton White House.”

Outgoing personalities often falter with respect to focus and attention to detail. They are overly susceptible to boredom with routine tasks and policy particulars. The good news is that in Dick Cheney, Bush has chosen the consummate organization man to fill the No. 2 slot in his administration. And as governor of Texas the president-elect has demonstrated a knack for delegating the more mundane aspects of day-to-day operations.

Political skill

Political acumen may well turn out to be the defining feature of the Bush presidency. Bush’s primary personality strengths are “people” skills. His outgoing orientation will be instrumental in rallying, energizing and motivating others. It also will help in building the necessary public and political support for implementing his policy initiatives.

Bush’s campaign slogan, “I’m a uniter, not a divider,” is more than just a platitude; it’s firmly rooted in the essence of his character.

Vision

Vision, in one sense, refers to the power to inspire. Bush likely will fall short of the rhetorically proficient presidents mentioned earlier. But equally important, vision “encompasses consistency of viewpoint,” writes Greenstein, who cites Ronald Reagan as the prototype of a visionary president “committed to a handful of verities.”

In this regard Bush, whose agenda as governor revolved around four key programs, sounds positively Reaganesque. Thus, regarding “the vision thing,” the problem with Bush will not be so much lack of principle as insufficient immersion in policy detail.

Strategic intelligence

While lacking the intellectual curiosity of Kennedy or Clinton, or the brilliance of a Richard Nixon, Bush’s intellect has been grossly underrated.

With a reported SAT score of 1,206, Bush likely equals or exceeds John F. Kennedy’s intelligence quotient, weighing in at 119. But, as Greenstein notes — pointing to the policy accomplishments of Truman and Reagan, “two presidents who were marked by cognitive limitations” — intelligence “as measured by standardized tests is not the sole cause of presidential effectiveness.”

The key to executive success is a strategic intelligence that cuts to the core of complex problems. This, in Greenstein’s judgment, was Eisenhower’s genius, despite “the jumbled syntax of his press conferences.”

The concern with Bush is that, unlike Kennedy, there is little indication of an

intrinsic quest for knowledge — be it a critical reading of history, an appreciation of great works of philosophy or literature, or something as mundane as digesting official briefings or background reports.

Emotional intelligence

It is unfortunate that failed leadership offers the most compelling illustration of the critical importance of personality in politics. The flawed presidencies of Lyndon Johnson, Richard Nixon, Jimmy Carter and Bill Clinton all serve as stark reminders of the pernicious effects of emotional mismanagement on

presidential performance.

In this regard, the major concern with respect to Bush is that outgoing personalities can be shortsighted and predisposed to impulsive and imprudent behaviors. They can be inclined to make spur-of-the-moment decisions. There is redeeming value, however, in the self-discipline that Bush displayed, belatedly, when after age 40 he started reigning in his unruliness.

Overall, political psychologists recognize that political outcomes are controlled by a multitude of factors, many of them indeterminate. Nonetheless, the study of personality in politics has advanced sufficiently to permit broad personality-based leadership predictions and to pinpoint a candidate’s specific strengths and weaknesses.

While our predictions remain far from perfect, we continue to work diligently to divine presidential intent and attain more clairvoyant levels of precognition.

Aubrey Immelman is a political psychologist and an associate professor of psychology at the College of St. Benedict and St. John’s University. You may write to him in care of the St. Cloud Times, P.O. Box 768, St. Cloud, MN 56302.

Follow Aubrey Immelman