Election results make one wonder: Was it personality or lucky timing?

By Aubrey Immelman

St. Cloud Times

November 19, 2000

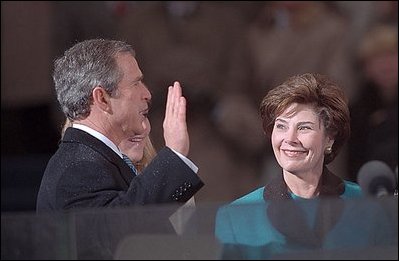

George W. Bush is sworn in as the 43rd President in an inaugural ceremony at the United States Capitol (Release P182-4). Public domain.

As I write this, the outcome of the 2000 presidential election still hangs in the balance as the nation awaits final results from the state of Florida. In stark contrast to the uncertainty surrounding the result of this closely contested presidential election, various prognosticators and self-proclaimed pundits — myself included — confidently predicted a clear outcome to the contest.

At a meeting of the Psychohistory Forum in New York City in March 1999, 20 months before the election, I predicted Al Gore would fail in his bid for the presidency, “provided the Republicans field an outgoing, relatively extraverted, charismatic candidate.”

Specifically, I contended that the vice president’s conscientious, introverted personality pattern augured poorly for his candidacy “in an era where political campaigns are governed by saturation television coverage and the boundaries between leadership and celebrity have become increasingly blurred.”

I went on to say that time and again since the first televised presidential debates in 1960, with the exception of Richard Nixon in 1968 and 1972, the more outgoing candidate with the greatest personal charisma and publicly perceived warmth or likability, has won.

Public opinion polls would later show that John McCain and George W. Bush, not Al Gore, best fit this profile.

In capturing 50 percent of the major-party vote — and possibly the presidency, pending the final tally in Florida — Al Gore exceeded my expectations. But the growing influence of the entertainment industry in shaping public perception was confirmed by the highly visible presence of Oprah, Regis, Leno, and Letterman along the 2000 election campaign trail.

If Gore exceeded expectations from a psychological point of view, he badly

underperformed from the perspective of conventional political-economic forecasting models.

As I pointed out in my Oct. 1 column, seven academic prognosticators in August at the annual meeting of the American Political Science Association, unanimously predicted that Al Gore would defeat George W. Bush decisively.

Using predictor variables such as economic growth, the public’s perception of economic well-being, the popularity of the incumbent president, and the candidates’ standings in public opinion polls, six analysts forecast victory margins ranging from 52.3 to 55.4 percent of the major-party vote for Gore, while a seventh predicted a Gore landslide, at 60.3 percent.

The lesson, in hindsight, is this: In the current cultural context, at the turn of the century, neither political-economic models nor a predictive model that relies exclusively on personality can accurately anticipate the outcome of closely contested presidential elections.

The remedy? Improve the accuracy of presidential forecasting models by acknowledging the pivotal role of personality in shaping candidate preference among independent and swing voters, and enter this variable into the equation.

The most practical personality dimension in this regard is introversion-extraversion, which best captures a candidate’s charisma, likability, and proficiency in retail politics.

That much was evident in the first presidential debate, which the overeager, socially tone-deaf Gore won on raw debating points but lost in the court of public opinion. His debate performance, keenly parodied on NBC’s “Saturday Night Live,” was widely perceived as supercilious and overbearing.

The point, simply, is this: A critical determinant of positive impression formation hinges on whether someone is perceived as warm and outgoing versus cold and retiring. In presidential politics, television plays a pivotal role in shaping these perceptions.

Rightly or wrongly, many voters perceive emotional distance as indifference and a lack of empathy, which elicits a reciprocal response toward the candidate. For Gore to have overcome this social bias — registering a slender majority of the popular vote — is testimony not of his strength as a candidate, but of the strength of the economy and the collective contentment of the American people.

The prototype of the presidential candidate who fails to ignite the public’s passion in an era of “made-for-television” elections, is the conscientious introvert — a character type that has not occupied the Oval Office since Jimmy Carter, and before him Herbert Hoover, Calvin Coolidge, and Woodrow Wilson.

Beyond their similarities of character, these candidates had something else in common: Their ascent to the presidency coincided with an unusual confluence of circumstances.

Wilson was able to win a plurality of the vote in the 1912 election when former Republican president Theodore Roosevelt threw his hat in the ring as a third-party candidate, handing a third-place defeat to the incumbent Republican, William Taft. “Silent Cal” Coolidge became president in 1923 when Warren Harding died in office.

Hoover had no political experience when the Republican Party nominated him in 1928 primarily on the strength of his reputation as an international organizer of relief agencies during and immediately following World War I. Finally, Jimmy (“I’ll never lie to you”) Carter was the product of a public backlash in the wake of Watergate.

And now in 2000, the longest economic boom in U.S. history may have produced — when all is calculated, litigated, and counted — the election of Al Gore as the next president of the United States. Or maybe not.

Unresolved: Did good economic times make the man or did personality in 2000 propel to the presidency an event-making man?

Aubrey Immelman is a political psychologist and an associate professor of psychology at the College of St. Benedict and St. John’s University. You may write to him in care of the St. Cloud Times, P.O. Box 768, St. Cloud, MN 56302.

Follow Aubrey Immelman