Is ‘New Rudy’ the Real Rudy?

By Aubrey Immelman

St. Cloud Times

June 4, 2000

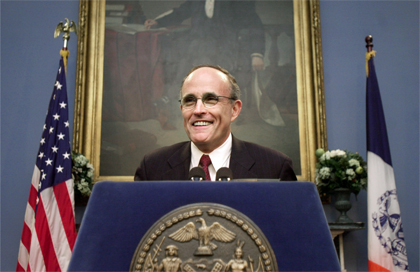

Rudolph Giuliani is seen while mayor of New York City holding a news conference at City Hall, New York, NY, April 27, 2000. (Photo credit: Chris Hondros / Newsmakers)

When New York mayor Rudolph Giuliani ended his Senate bid on May 19, speculation was rife about the “new Rudy.”

As the New York Daily News breathlessly editorialized on May 20, “Rudy Giuliani’s announcement that he is stepping out of the race for U.S. Senate, as moving as it was riveting, revealed a side of his personality rarely seen in public. Yet there could have been no better illustration of why he would have been a superb candidate. It showed him to be not only honest and straightforward, but also compassionate and deeply committed to the people of New York.”

Then, on May 25, Sherryl Connelly, in a Daily News opinion column titled “No more Mr. Ice Guy,” wrote: “I’d give anything for this not to be happening, but I’m developing feelings for Rudy Giuliani. … The new Rudy has been popping up here, there and everywhere as a hard man humbled. Which is alluring. … Rudy has been letting his inner human out.”

Not so fast.

Personality, by definition, denotes a person’s consistent, distinctive patterns of thinking, feeling, acting, and relating to others — and the “new Rudy” persona is distinctly out of character.

Abrupt, drastic changes in behavior are more indicative of an individual’s response to powerful situational forces than of lasting personality change, and more often than not reflect transient, temporary adaptations to an immediate crisis.

Claims of a new Rudy notwithstanding, logic dictates that Giuliani remains the dominant, controlling, aggressive personality whose combative orientation was as instrumental to his successful track record as a prosecutor as it has been in his crusade to clean up the mean streets of New York City.

But personality style can be a double-edged sword. During his tenure in the mayor’s office, Giuliani has shown a potential for self-defeating rigidity and an unwillingness to compromise, with a penchant for berating his critics and assailing subordinates not acting fully in accordance with his wishes.

While those qualities may be effective in getting the job done in New York City, such fiery zeal may not be the right stuff for success in the U.S. Senate, revered by some as “the world’s greatest deliberative body.”

Giuliani may be better suited for an executive position such as mayor or governor, but the venerable legislative body that is the U.S. Senate is no place for a bellicose brawler in which to advance his political ambitions.

Unless, of course, there is substance to the speculations of a new Rudy emerging from the ashes of his aborted Senate bid in the face of a life-threatening crisis.

Giuliani, in announcing his decision to quit the race, noted that the notion of a new Rudy was “silly,” saying, “I think maybe it’s going to be a different [Rudy], maybe somebody who grows from the fact that you confront your limits, you confront your mortality. You realize you’re not a superhuman and you’re just a human being.”

Can the leopard change his spots? Studies suggest that close to 40 percent of the variance in personality and social behavior is biologically inherited. Biology, clearly, is not destiny; experience creates considerable wiggling room for personality change.

However, personality crystallizes quite early in life and is fairly fixed by the end of the third decade, despite popular notions of life’s “seasons” or “passages” such as the “midlife crisis” or the “empty nest syndrome.”

Without denying the importance of critical events in human lifespan development, basic personality patterns are remarkably stable by midlife. In a sense, the more things change the more they remain the same.

So, can the contentious, combative Giuliani tame the beast within?

Fundamentally, no. But the fateful events of the past month have shown that the firebrand Giuliani is able to take stock of his priorities, see the bigger picture, and curtail his baser, more aggressive impulses.

If his brush with mortality teaches Rudy to restrain the beast and harness its power more skillfully, he will emerge from this crisis as a formidable force in politics — no longer fuming but still with that old fire in the belly.

Aubrey Immelman is an associate professor of psychology at the College of St. Benedict and St. John’s University, where he directs the Unit for the Study of Personality in Politics, a faculty-student collaborative project with the mission of conducting psychological assessments of candidates for political office and disseminating the findings to professionals, the national media, and the public. Joshua Jipson, junior English major from Lakeside, Wis., contributed to this article.

Follow Aubrey Immelman