Relying on loyalty could hurt Bush

By Aubrey Immelman

St. Cloud Times

December 29, 2000

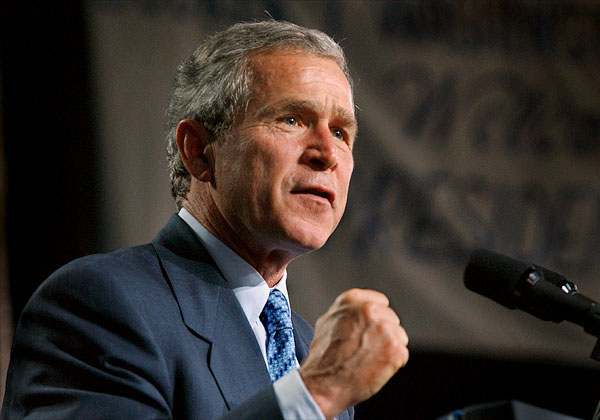

President George W. Bush makes remarks during a visit to Booker T. Washington High School in Atlanta, Ga. Jan 31, 2002. WHITE HOUSE PHOTO BY ERIC DRAPER

When Bill Clinton ran for president in 1992, the nation knew all about Gennifer Flowers. Later, it would learn much more than it needed to know about Monica Lewinsky.

Whereas a president’s policy preferences and polls numbers are prone to change, his deeply etched personal qualities are remarkably consistent. In leadership studies, it is precisely this stability that imbues character and personality insights with predictive power in anticipating the shape of things to come.

Thus, Knight Ridder Newspapers could report earlier this month, “Bush offered a glimpse of the leadership style he intends to bring to the Oval Office in a series of interviews … during his presidential campaign. The president-elect delegates authority, detests long-winded briefings and rewards loyalty.”

As was the case with his predecessor, President-elect Bush in the course of his campaign telegraphed the personal proclivities that would govern critical aspects of his presidential leadership. Where Bill Clinton had a penchant for personal risk-taking, George W. Bush’s particular brand of immoderation lies in the premium he places on trust and loyalty — specifically, his expectation of unwavering personal loyalty and his reciprocal trust in the judgment of his closest advisers.

Exhibit 1. Bush, announcing his selection of Al Gonzalez as White House counsel: “I understand how important it is to have a person I can trust. … I know first-hand I can trust Al’s judgment.” In 1996, as Gov. Bush’s general counsel, Gonzalez helped Bush avoid jury duty in a drunken driving case that could have forced the governor to disclose his own 1976 DUI arrest. Instead, the story broke in the press just days before Election Day.

Exhibit 2. Bush, on naming Karen Hughes counselor to the president: “She has been at my side and I trust her a lot. … She has got enormous judgment as well.” Hughes, Bush’s longtime confidante, press aide, and communications director had previously known about the DUI incident that Bush imprudently failed to disclose during his presidential campaign.

Exhibit 3. The New York Times, on Bush’s nomination of “lifelong friend” Don Evans as commerce secretary: “… in naming him, Mr. Bush kept his most loyal supporter at his side in Washington.”

This tendency to favor trust and loyalty was highlighted in his presidential campaign when Bush tapped someone whose loyalty he could trust implicitly — the secretary of defense in his father’s administration — to lead his vice-presidential search, only to select this very person, Dick Cheney, as his running mate.

Fortunately, personal loyalty and fitness for the position are not mutually exclusive. And certainly, no one can fault a president for choosing qualified, experienced officials and advisers whose loyalty and judgment he absolutely trusts. But surrounding oneself with a coterie of trusted allies and loyalists has its risks.

For one thing, it can breed insularity, a prime catalyst for defective decision making.

In his book “The Presidential Difference,” political scientist Fred Greenstein writes that a key ingredient of a president’s organizational capacity is “his ability to forge a team and get the most out of it, minimizing the tendency of subordinates to tell their boss what they sense he wants to hear.”

Greenstein cites Dwight Eisenhower as the epitome of a president with the personal ability to avail himself “of a rich and varied fare of advice and information.” Eisenhower excelled in generating a diversity of policy options, clearly delineating critical disagreements, and subjecting them to focused debate.

Here’s the New York Times, commenting on the White House role of counselor to the president designee Karen Hughes: “One of Ms. Hughes’s assets is her loyalty to Mr. Bush. She is fiercely protective of him and has not given any hint that she believes he can do any wrong.”

Given the pitfalls of blind loyalty, it is encouraging that Hughes is on record as saying that she feels “absolutely free to disagree” with her boss. And, in accepting her White House appointment, she publicly promised always to give the president her “unvarnished opinion.”

Outgoing, personable leaders such as President-elect Bush have a propensity for favoring personal connections, friendship, and loyalty over competence in their staffing decisions and political appointments. While this tendency in and of itself is not sufficient to undermine presidential leadership, it does have important implications with regard to a president’s oversight functions.

This holds especially true for a leader such as George W. Bush who dislikes dealing with policy minutiae, discourages excessively detailed briefings, and prefers to delegate authority. Unless such leaders reward constructive criticism and diversity of opinion along with loyalty, as co-equal elements of an effective presidential advisory system, they run the risk of defeating their best efforts at protecting the integrity of the office and guarding public resources against improper and injudicious appropriation.

Clearly, the first challenge for the new president is to demonstrate his ability to draw a line in the sand, so to speak, between personal loyalty and competence for the position.

Aubrey Immelman is a political psychologist and an associate professor of psychology at the College of St. Benedict and St. John’s University. You may write to him in care of the St. Cloud Times, P.O. Box 768, St. Cloud, MN 56302.

Follow Aubrey Immelman